3 Ways To Incorporate Food in Your Fiction

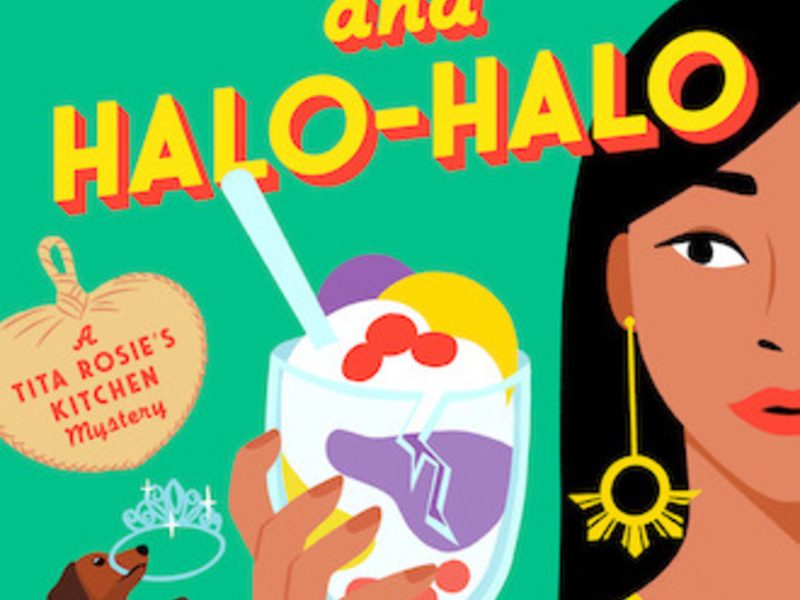

Food and books are probably the greatest pleasures of my life. So imagine my excitement when I found out there was an entire sub-genre that combined my two loves: culinary cozy mysteries. I was so happy to contribute my own spin on the genre last year with my debut novel, Arsenic and Adobo, which is part of the Tita Rosie’s Kitchen Mystery series. My books center around a family-run Filipino restaurant in a small town just outside of Chicago (and murder, but this article isn’t about that).

(Mia P. Manansala: On Savoring Positive Feedback)

Just like sex scenes and fight scenes, eating scenes are a way to move along the plot, incorporate sensory detail, develop the world, and tell you more about the characters and their relationships—with food, with themselves, and with the people around them. I could write entire articles on each section listed below, but here are some brief examples:

Sensory Detail

- Smell. Is the aroma of this dish connected to a memory? Is it pungent and overpowering? Savory and mouthwatering? Tangy and refreshing? Sweet and comforting? Describing the scent that fills the room can help set the scene.

- Touch. Many people I know are texture eaters, so describing the mouthfeel of a dish adds another layer to the experience. Is the coating on the tempura earth-shatteringly crisp, or sad and soggy? The flan or crème brûlée your character is sampling at a family party, is it like silk as it slips down their throat, or tough and full of air holes? What is the temperature like on the various foods and how does that affect how your characters experience them?

- Sight. People often eat with their eyes. Is your character at a Michelin-starred restaurant where the plating is absolutely dazzling? Are they eating at the school cafeteria and the food is just slopped on their plate, all messy and unappetizing?

- Sound. This is usually the most difficult sense to incorporate when talking about food, but this is where you get to stretch your imagination. Are you at a Filipino restaurant and the server just dropped off a plate of sisig, the cast iron plate so hot that the dish sizzles audibly while crisping the pork? Is there a scrape of utensil against plate as you stir the raw egg into the dish, maybe a hiss as you squeeze fresh calamansi or lemon over the concoction? Are you sharing hot pot with friends and the bubbling cauldron matches the bubbling energy of conversation? Maybe the screech of a knife as it cuts through a tough steak echoes the discord between you and your dining partner?

Characters and Relationships

In my second book, Homicide and Halo-Halo, my protagonist is feeling down until her aunt brings her a plate of chicken. But it’s not just any chicken. The familiar aroma, which she hasn’t smelled in almost two decades, has her bolting out of bed. “Is that Mommy’s chicken?” she asks. Her mother died when she was eight. That scene plays with scent and memory, reveals backstory, and shows what the relationship was like, not just between Lila and her mother, but her mother and the family she married into.

IndieBound | Bookshop | Amazon

[WD uses affiliate links.]

While I usually use food as a source of love and happiness, not everyone has the same experience. Explore your characters’ relationship with food: What brings them joy? What tortures them? What memories/feelings/reactions does a particular dish evoke? Do they have dietary restrictions? If so, how do they navigate them and how do the people around them accommodate them (or not)? How do they behave around food in group settings?

World-building

Giving your readers a strong sense of place isn’t only about the topography—who are the people that populate the world of your story? In Arsenic and Adobo, Lila investigates the town’s restaurateurs, each representing a microcosm of different ethnic enclaves, similar to how many Chicago neighborhoods are set up.

There are so many ways you can use food as world-building that I could write an entire article just on that! But here are three ways:

- Familiar vs. Unfamiliar. Everybody thinks they know what a hot dog is … until they come to Chicago and try to put ketchup on one. Or go to Chile and get a completo, topped with avocado, tomato, mayonnaise, salsa, and much more. Or visit a South Korean street cart and get a hot dog on a stick wrapped with French fries. What can you say about your world and the characters in it by contrasting what’s familiar with what isn’t?

- Diaspora and Authenticity. The question of what “counts” as “real” [insert ethnicity] food is a conversation that surfaces again and again in ethnic and foodie spaces. It’s a particularly fraught one because it touches on generational, geographical, and familial differences. In Arsenic and Adobo, my protagonist, Lila, and her grandmother butt heads over this difference. Lila loves creating fusion Filipino desserts while her grandmother prides herself on doing things the traditional way, the “right” way in her mind. This causes a lot of friction between the two, with Lila considering her grandmother closed-minded until she realizes that food is the one tangible connection her grandmother still has to her homeland. Tradition, and the time-consuming way her grandmother insists on preparing her sweets, may seem stifling and unnecessary to Lila, but it’s a source of comfort to her grandmother. A plate of food is never just a plate of food.

- Power and Class/Societal Differences. Food is political. Who has access to it? Who grows and raises it? Who benefits from it? Even doing a simple snobs vs. slobs dynamic (she wants the fanciest charcuterie board, he’s happy with generic brand Lunchables. One person brought a spicy shrimp curry to the potluck and nobody is touching it, but that tater tot casserole is getting a workout, etc.) can give you insight into the world these characters inhabit. There’s a lot to unpack with this topic, so if this interests you, the podcast, The Racist Sandwich, delves deeper and more critically into this idea.