Writing Mistakes Writers Make: Rushing the Editing Process

Everyone makes mistakes—even writers—but that’s OK because each mistake is a great learning opportunity. The Writer’s Digest team has witnessed many mistakes over the years, so we started this series to help identify them early in the process. Note: The mistakes in this series aren’t focused on grammar rules, though we offer help in that area as well.

Rather, we’re looking at bigger picture mistakes and mishaps, including the error of using too much exposition, neglecting research, or researching too much. This week’s writing mistake writers make is rushing the editing process.

Writing Mistakes Writers Make: Rushing the Editing Process

Listen, I get it. You wrote something amazing, you’re super proud of it, and you just want to wrap it in a nice little bow and get it off to your readers so you can work on the newest project that’s lighting you up. A cursory spell-check and making sure your formatting looks good should be enough to get this thing out to your readers, right?

And you might even think that your story doesn’t need editing. If that’s you, I would love to refer you to this wonderful article by Senior Editor Robert Lee Brewer: Writing Mistakes Writers Make: Refraining to Revise Writing.

But you’re doing yourself and your story a disservice by blowing through the revision process. It’s like someone telling you that they’re giving you a pearl and then handing you an oyster. Like, sure, you can do the work to get the pearl out yourself, but you weren’t promised an oyster … you were promised a pearl.

Naturally, your story has a few kinks that need to be worked out, even if you’ve done a cursory read-through after finishing the draft. And revisions can seem overwhelming, especially when you’re still wrapped up in post-writing exhaustion. However, approaching your revision process like a professional editor will up-level your work and give your audience a better reading experience.

Mistake Fix: Three-Part Revisions

When an author hands me a draft, as their editor, there’s a three-part process I know I’m about to dive into:

- Developmental edits

- Line edits

- Proofreading

Don’t worry if you’re not familiar with these terms; a lot of writers, especially ones new to the industry, don’t recognize them.

Developmental edits are where you approach the story from the big picture. If you have a beta reader, this is where you’ll hand your manuscript off to them so they can analyze your draft for things like plot holes, scenes that go on for too long, scenes that need to be expanded, etc. Find yourself resisting the idea of having a beta reader? You might want to check out this article: Writing Mistakes Writers Make: Not Accepting Feedback on Your Writing. Or maybe you’re interested in using a beta reader but you’re not sure about the best way to receive feedback? This article might be helpful: Writing Mistakes Writers Make: Not Asking Questions in the Drafting Process.

If you’d like to tackle developmental edits on your own, I recommend shelving your draft for a short time (give yourself a deadline of 5-7 days, maybe), and then picking it up and reading it through the way that a new reader would. Are your themes coming through clearly? Does your timeline make sense? Is there a clear emotional arc for your character? Once you have a list of these big-picture items that need addressing, you can dive back into your manuscript and hammer out those kinks.

This is also the stage where I recommend that authors hire a professional sensitivity reader to review their work, even if you’ve done a developmental edit on your own. A sensitivity reader is a professional editor who is trained to look for offensive content, misrepresentation, stereotypes, bias, lack of understanding, etc. You can find these professional editors for hire on a site like Reedsy.

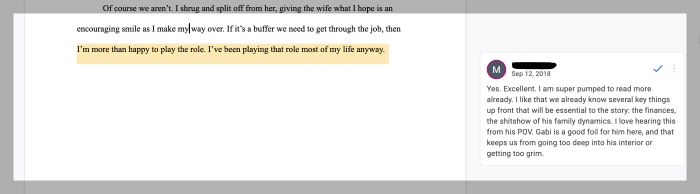

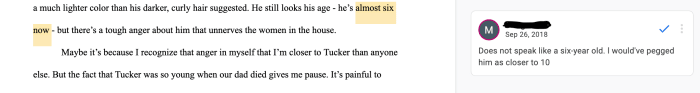

Here are two images of what my beta reader’s developmental edits look like:

The second phase is line editing. This will be a lot of your heavy lifting, as you’ll be going through your draft line by line and looking at the flow of your story. At this stage, you’re not looking at grammar; you’re looking at style. Do you tend to include a lot of long sentences in a row? Break some of those into smaller sentences to keep your reader engaged. Does your dialogue sound natural? Is your narrator’s voice consistent? I recommend that you actually read your manuscript out loud at this stage—it’ll eat up a lot of time, but you’ll catch all sorts of stylistic weirdness that you wouldn’t by reading silently. It’s a tried-and-true method I’ve used with a lot of my authors, and it’s always worked.

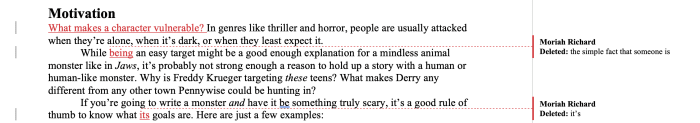

Here’s an example of what my line edits look like:

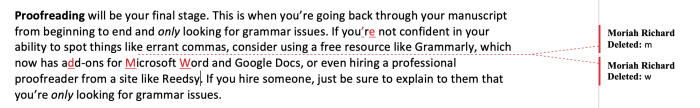

Proofreading will be your final stage. This is when you’re going back through your manuscript from beginning to end and only looking for grammar issues. If you’re not confident in your ability to spot things like errant commas, consider using a free resource like Grammarly, which now has add-ons for Microsoft Word and Google Docs, or even hiring a professional proofreader from a site like Reedsy. If you hire someone, just be sure to explain to them that you’re only looking for grammar issues.

Here’s an example of proofreading:

The key is not to rush this process and not let yourself get stuck in it. Once you finish one part of the editing process, make a promise to yourself to not go back unless it’s a dire emergency. If you’re in the proofreading stage and realize that you somehow deleted three important paragraphs from the second page of chapter 3, fine, go ahead and insert them, line edit them, and then continue your proofreading. But if you’re line editing and find yourself constantly coming up with new ideas and wanting to write whole new subplots or delete large swaths of text, it could be a sign that you’re not ready for the editing part of this book’s journey; give yourself more time in the writing stage or commit to the story as it stands.

And if you find yourself getting stuck in revisions, ask yourself if it’s really the story you’re unhappy with or if you’re giving into fear. I’ve worked with plenty of authors in my career who can’t seem to get the project over the finish line; heck, I’m a serial non-finisher of longer works as well. In my experience, that comes from a place of fear. Understanding exactly what you’re afraid of—is it being vulnerable in front of others? Fear of failure? Fear of success?—you can take steps to address that fear and get back to work. To help you get started on that process, I will leave you with two more articles from this series: