6 Things Every Writer Should Know About Sylvia Beach and Shakespeare and Company

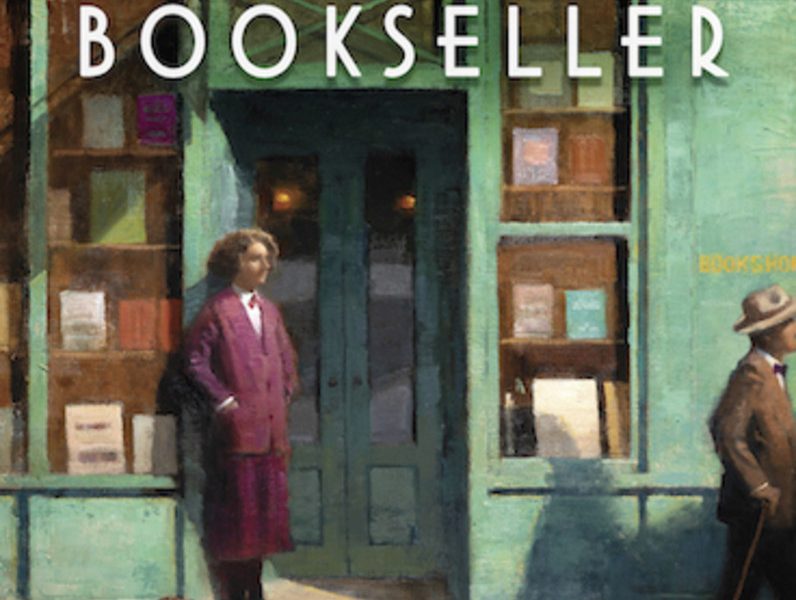

You know, it’s funny that it took me so long to write The Paris Bookseller—I’ve been carrying Sylvia’s story around inside me since I was 20 years old, which is when I read her memoir, a slim volume called Shakespeare and Company. I found an old paperback of it in a used book bin outside one of the many bookstores in my college town, and since I was an English major obsessed with the 1920s, I read it right away.

(Kerri Maher: On Playing the Long Game)

I was charmed by Sylvia’s recollections of her bookstore and lending library and the famous writers who frequented it, and I was fascinated by her remarkable publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses after it had been banned in an obscenity trial in 1921. She called herself a “booklegger,” because like the bootleggers of Prohibition she, too, smuggled an illegal commodity into the U.S.

Here are six things every writer should know about Sylvia Beach and Shakespeare and Company.

Shakespeare and Company was really two stores. Sort of.

Sylvia Beach was inspired to open her own store by a French-language bookstore and lending library in the Left Bank, La Maison des Amis des Livres at 7 rue de l’Odéon, which was opened by Adrienne Monnier in 1915. It was one of the first bookstores in France to be run by a woman, and it quickly became the meeting place of bohemian writers and artists like Jean Cocteau and Andre Gide. Soon after meeting in 1917, Adrienne and Sylvia became lovers and partners in all things including bookselling.

When Sylvia opened Shakespeare and Company across the street from Adrienne’s on the rue de l’Odéon, the two women called their literary haven Odéonia, and James Joyce affectionately referred to it as Stratford-on-Odéon. The two stores were truly two halves of a whole, offering readers the best of literature in French and English, hosting readings, and providing hospitality to writers in need.

Shakespeare and Company, Paris, has had three locations and three owners.

Sylvia Beach opened the first iteration of her store around the corner from La Maison, at 8 rue Dupuytren, in November 1919. When the opportunity arose to establish herself across the street from Adrienne in 1921, Sylvia moved to the shop’s most famous address, 12 rue de l’Odéon. She had to close in 1941 when Nazis threatened to shut it down themselves, and she never reopened.

IndieBound | Bookshop | Amazon

[WD uses affiliate links.]

Then, in 1951, another enterprising American bookseller named George Whitman opened a bookshop called Le Mistral at 37 rue de la Bûcherie, where Sylvia herself was a regular. On the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birthday in April of 1964 (two years after Sylvia’s death), he rechristened Le Mistral Shakespeare and Company. This store is in many ways an homage to Sylvia’s original, and is owned and operated today by George’s daughter, whom he named Sylvia.

In the ‘20s and ‘30s, if you were an American in Paris, Sylvia would hold your mail for you.

In A Moveable Feast, Ernest Hemingway said of Sylvia, “no one I ever knew was nicer to me.” One of the many kindnesses she did for the Lost Generation writers was to act as a post office box, a sort of permanent address in Paris, which was quite handy for many writers as they moved around the city and Europe at large, so often in search of the right accommodation at the right price.

She might have published Ulysses, but she wouldn’t publish your novel.

Sylvia took an enormous personal and financial risk to publish Joyce’s watershed novel Ulysses after it was banned in an obscenity trial in 1921. But perhaps because publishing Ulysses was such a one-of-a-kind adventure, she never published another writer, though many others, including D.H. Lawrence, asked her to.

She let James Joyce write a third of Ulysses on the page proofs!

Which drove up printing costs substantially, and even made the printer threaten to quit. Sylvia is the first to admit, in her own memoir, that she was not an experienced publisher, and she doesn’t recommend that anyone publish a novel the way she did Ulysses, but she wouldn’t have had it any other way. Though her publication of Ulysses was fraught with peril, it was also immensely rewarding.

And by the way writers, these days your publishing contract is likely to say you’re not allowed to change more than 10% of your novel at the page proof stage, or YOU will be charged to reset the type.

Shakespeare and Company should be your first stop in Paris—then and now.

In the 1920s and ‘30s, Sylvia knew everything there was to know about Paris, especially for the American expats and tourists. She found them accommodations, provided recommendations for work and play and dining, and of course she was always ready with a subscription to the library portion of Shakespeare and Company, which was especially useful for the writers who didn’t have enough money to purchase books.

*****

Today’s Shakespeare and Company is in a different location and run by another American, Sylvia Whitman, but it is an equally magical shop, full to the brim of terrific English-language literature for purchase. The location is nothing short of stunning, too, at “Kilometre Zero,” right on the Seine across from Notre Dame. You can buy books, then order a coffee at the adjacent café, and drink it as you admire the centuries-old cathedral that burned so horribly in 2019, but is being valiantly repaired today.

Join Donna Russo Morin to learn the definition of historical markers and how and where to unearth them. And uncover the tools to integrate history, research, and the fiction plot arc. Most of all, find out how to honor verisimilitude—the goal of any historical writing—and avoid the dreaded anachronism.