Owls NFTs Are Driving a Resurgence in ASCII Art

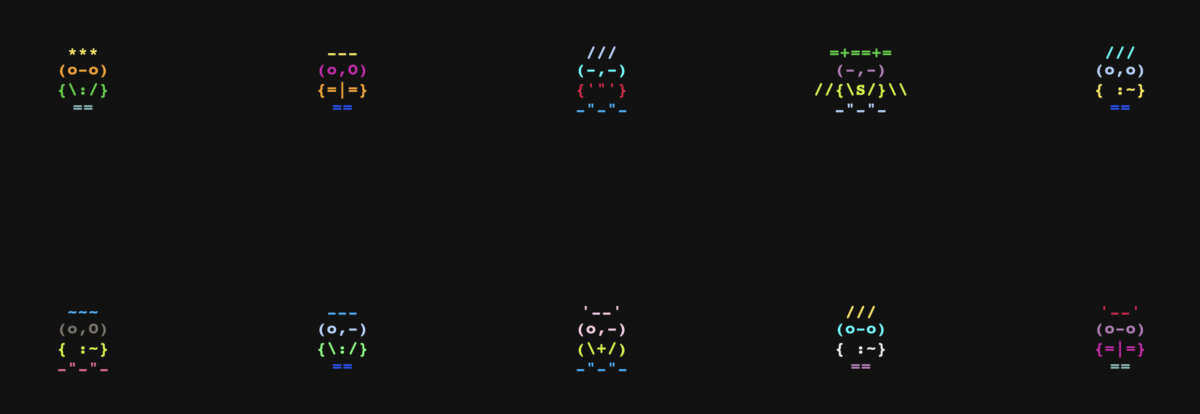

Owls NFTs have been on an absolute tear recently. Having dropped on March 3, the 10,000-piece collection of randomly-generated colorful text art owls has already done more than 11,000 ETH ($17 million) in trading volume on the secondary market and currently has a floor price of 0.184 ETH.

Little is known about the collection, whose Twitter account is just a month old and whose creator recently self-doxxed to reveal that they go by Rei. What is certain is that the project has rekindled interest in ASCII art NFTs and other on-chain projects that make up a remarkable part of the history of crypto art.

In contrast to their novelty, Owls NFTs come from a long line of minimal, text-based projects and experiments that hold a crucial place in the often-overlooked annals of Web3 and whose influences extend far beyond the blockchain itself. More so than any project in recent memory, Owls’ popularity has given the community cause for reflection on the nature of that history and how trends grow, fade, and reemerge in the crypto art ecosystem.

The ASCII meta has deeper roots than you think

Before diving into the newly resurgent meta around ASCII and similar, text-based visual art media, we must first understand their origins. ASCII (the American Standard Code for Information Exchange) is a common character encoding format for text data online, whose history dates back to 1963.

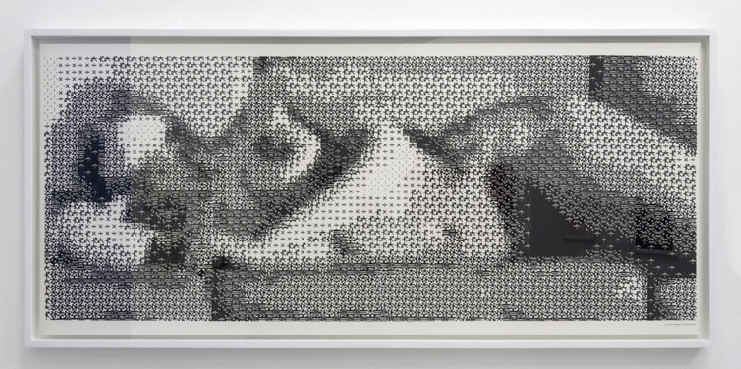

One of the very first recorded pieces of ASCII art was created by computer art pioneer Kenneth Knowlton who worked for the famous Bell Labs and is credited with laying the foundation for computer-generated imagery in TV and film. Alongside Leon Harmon, a cyberneticist who also worked at Bell, the two created Computer Nude (Studies in Perception 1) in 1966.

But this style of text-based artistic experimentation precedes the 1960s by a wide margin. Diving even deeper into history, we find that creative expression in the spiritual and aesthetic vein of ASCII art goes as far back as the 1890s when people would use the then newly-invented typewriter to engage in what some have labeled “artyping.”

Given this legacy, it’s fitting that some of the earliest forms of crypto art came to be through the medium of ASCII. Among the projects that have the honor of holding that title is the storied NFT collection Punycodes, NFT art that emerged out of the Namecoin blockchain more than a decade ago.

Namecoin had launched in early 2011 as a decentralized domain name system (DNS) to store domain registration information. As Bitcoin was heralded as a system that “freed money,” so, too, was Namecoin billed as creating a liberated, decentralized naming system that was censorship-resistant; centralized organizations and governmental bodies couldn’t take down an internet domain that was registered on the blockchain. For a small fee, Namecoin users could register a domain on-chain, effectively creating an NFT that stored that domain’s data.

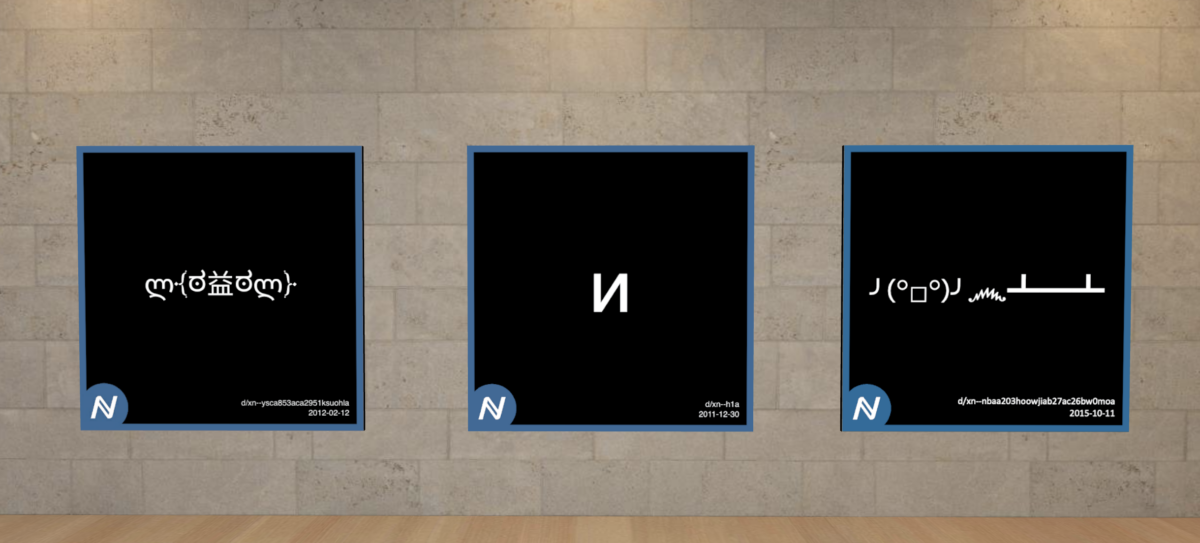

This development would prove to be a cornerstone in the history of NFTs. Having created a way to store basic data on the blockchain, Namecoin developers had inadvertently created a new artistic canvas. Early Namecoin DNS experimenters began using the chain to store simplistic visual information on their domains using an encoding language called Punycode. With Punycode, experimenters could now add symbols, emojis, and ASCII characters to the Namecoin chain.

The result was Punycodes, some of the first visual art NFTs in the history of crypto art. It’s important to note that this “collection” of NFTs didn’t come about with the intentionality that project developers create a collection today. Rather, Punycodes was more of a happy accident that saw a new technological capability collide with human curiosity and playfulness. This stands in stark contrast to Jennifer and Kevin McCoy’s Quantum, for example, which is widely regarded as the first intentionally-made piece of generative NFT art (a work that was also originally stored on Namecoin).

While there is some debate about whether or not Punycodes are true “NFTs” or “art NFTs” in the sense that we know them as today, their pedigree and legitimacy are at least partially backed up by Vitalik Buterin himself, who, in Ethereum’s whitepaper, refers to Namecoin’s domain names as “non-fungible assets.” These NFTs are a vital part of crypto art’s history because they expanded the limitations of what could be done using blockchain tech.

ChainFaces enters the chat

Punycodes’ cultural impact continues to reverberate through Web3. Fast forward to January 2020, and the on-chain generative ASCII collection of text “faces” called ChainFaces arrived on the scene as a kind of successor to Punycodes.

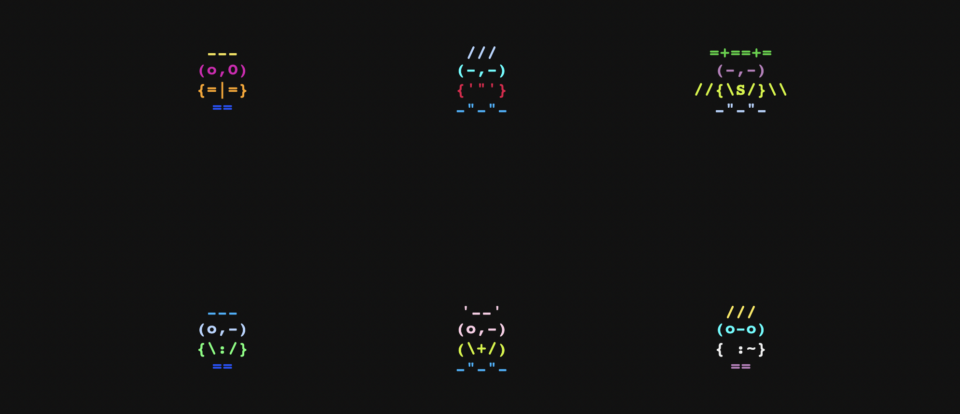

The collection’s creator, Nate Alex, a Web3 builder, creator, investor, and founder, used an algorithm to generate the 10,000 faces in the collection from text and emojis. Alex would later reveal the second stage of that collection’s evolution, ChainFaces Arena, a kind of NFT battlefield in which holders can enter their NFTs for the chance to win a share of a crypto reward.

During the month-long tournament, 17,031 ChainFaces did battle. A total of 12,775 “died” and were removed from the circulating supply of the collection, and those that remained had generative scars applied to their tokens. Like Owls, ChainFaces’ text-based, fully on-chain nature has its lineage in projects like Punycodes. Notably, ChainFaces has seen a marked surge in sales and trading volume recently, some of which may be attributable to the attention Owls has brought it and other projects like it recently.

Autoglyphs is another project that many view as the first “fully on-chain” generative art project on the Ethereum blockchain. Created by CryptoPunks creators Larva Labs in 2019, Autoglyphs is a variation of ASCII art stored within the same contract that allows for the art’s very creation. Only 512 pieces exist, and the NFTs in the collection remain widely sought-after.

The Moonbirds connection

Apart from shining a spotlight on both on-chain and ASCII-based art, Owls has caught the attention of the Moonbirds community, with some holders of the Proof Collective NFTs gladly welcoming the bird-themed tokens into their collections. And with Proof going through a significant public recalibration regarding the direction, cohesion, and significance of the NFTs under its banner, several owl-themed projects have been (somewhat jokingly) asserting themselves as the new avian rulers of the bird NFT scene.

Community reactions to the whole Owls-induced shake-up have been varied. Some, like artist Bryan Brinkman, couldn’t help but note the nostalgia in the way metas form and repeat over time in the NFT space. Others found an opportunity to poke fun at the fickle nature of a Web3 community that stumbles over itself for simplistic text art projects while remaining comparatively lukewarm toward the launch of an NFT project backed by animation giant Pixar.

Putting it all in perspective

Last October, self-described data scientist Chainleft compiled a timeline of some of the most significant on-chain projects in NFT history, showcasing 2011’s Punycodes, 2015’s Linagee Name Registrar, ChainFaces’ 2020 creation, as well as 2021’s on-chain game EtherOrcs, among several others. There are dozens more that have helped establish precedence for what came after in the crypto art space, and Owls is as steeped in that legacy as any other.

While Owls’ trading volume and popularity are undoubtedly impressive, the project’s rise has given the crypto art community something far more valuable: a reason to reflect on the ecosystem’s history and a chance to consider its future. That matters a great deal in a space that seemingly demands its inhabitants move and think at a constant breakneck pace while always being on the lookout for the next big thing. Ultimately, Owls’ on-chain ASCII art is a love letter to the earliest foundations of the NFT space as we know it today.

The post Owls NFTs Are Driving a Resurgence in ASCII Art appeared first on nft now.